Evaluation of the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research

Final Report

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings

- 4. Recommendations

- Appendices

This report has been prepared by KPMG LLP (“KPMG”) for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research ("Client") pursuant to the terms of our engagement agreement with Client dated August 10, 2015 (the “Engagement Agreement”). KPMG neither warrants nor represents that the information contained in this report is accurate, complete, sufficient or appropriate for use by any person or entity other than Client or for any purpose other than set out in the Engagement Agreement. This report may not be relied upon by any person or entity other than Client, and KPMG hereby expressly disclaims any and all responsibility or liability to any person or entity other than Client in connection with their use of this report.

© 2016 KPMG and the KPMG logo are registered trademarks of KPMG International, a Swiss entity

List of Acronyms

- ACAHO

- Association of Canadian Academic Healthcare Organizations

- ACCESS

- ACCESS Open Minds

- CCTCC

- Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre

- CD

- Capacity Development

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CLAHRC

- Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care, UK

- CT

- Clinical Trials

- EAC

- SPOR's External Advisory Committee on Capacity Development

- ED

- Executive Director (typically for SUPPORT Units)

- FP7

- Seventh Framework Programme of the European Union

- GBF

- Graham Boeckh Foundation

- HC

- Health Canada

- KI

- Key Informants

- MRC

- Medical Research Council, UK

- NICE

- National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence, UK

- NSC

- SPOR National Steering Committee

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PCORI

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute

- PE

- Patient Engagement

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PIHCI

- Pan-Canadian SPOR Network in Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations

- PMS

- Performance Measurement Strategy

- POR

- Patient-Oriented Research

- REB

- Research Ethics Board

- SPOR

- Strategy for Patient Oriented Research

- TPMI

- Newfoundland Translational and Personalized Medicine Initiative

Executive Summary

Overview

This report presents the findings from the evaluation of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) contributions to Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR). Although many of the SPOR partners were engaged in the evaluation, the evaluation was of CIHR’s contribution to SPOR only.

The SPOR evaluation covers the period from 2010-11 to 2015-16 and was scoped to address the evaluation elements outlined by Treasury Board related to program relevance, design and delivery, and performance to meet accountability requirements and additionally to inform program decision-making. Due to SPOR’s early stage of evolution, the evaluation focused on the deployment of SPOR core elements and short-term progress towards objectives.

SPOR Context and Profile

Patient-oriented research (POR) refers to a continuum of research that engages patientsFootnote 1,Footnote 2 as partners, focuses on patient priorities and improves patient outcomes individually and in communities such as vulnerable populations. This research, conducted by multidisciplinary teams in partnership with relevant stakeholders, aims to apply the knowledge generated to improve healthcare systems and practices. It involves ensuring that the right patient receives the right clinical intervention at the right time, ultimately leading to better health outcomes.Footnote 1

Announced in 2011, SPOR is a ten-year national Strategy. It encompasses five core elements:

- SUPPORT Units: specialized, multidisciplinary research service centres located in provinces and territories across Canada;

- Networks: pan-Canadian research networks that represent a collaboration of patients, health service providers, policy/decision makers, and health researchers;

- Capacity development: targets activities for training and support for POR;

- Patient engagement: supports efforts to engage patients in a meaningful way through active collaboration in governance, priority setting, and the conduct of research; and,

- Clinical trials: an element targeted to improve the clinical trials environment in Canada, primarily through the Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre.

While CIHR plays a leadership role within SPOR, it engages a broad coalition of stakeholders from across Canada.

Each SPOR element has been developed and implemented within varying timeframes. Although SPOR planning, design, partnership development, and foundational elements have been in place since its creation in 2010-11, several SPOR core elements have been in place for less than two years, with most only being active for one year at the time of the evaluation. Overall, SPOR is still in early stages of being implemented to scale and the results of this evaluation, particularly results related to intended outcomes, need to be interpreted with this condition in mind.

Findings

The evaluation found that SPOR is relevant to addressing Canadian health systems needs for integrating research into care. Key findings include:

- SPOR encompasses the elements and activities required to address areas in need of support for POR, such as enhancing access to common resources, increasing collaborations among stakeholders and facilitating patient involvement.

- SPOR is consistent with federal government and CIHR priorities, being a direct extension of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Act, which specifies CIHR’s mandate to improve the health of Canadians.

- SPOR is aligned with international trends towards employing POR models and approaches.

- It remains important for the federal government, through CIHR, to play a role in advancing the POR model in Canada.

- SPOR complements POR activities undertaken by the provinces and territories, helping to fill gaps in current programming, resources, methods and capabilities.

Some elements of the design and delivery processes for SPOR were found to be effective, but areas for further improvement were also identified.

The design and delivery elements found to be effective include:

- National governance mechanisms are generally strong with key success factors being the national composition that facilitates inter-jurisdictional learning and promotes a “let’s discuss together” approach.

- The consideration of provincial/territorial priorities and needs in the development of the SUPPORT Units in particular are a strength of the flexible approach CIHR has taken.

- Stakeholder engagement is believed to be “exceptional” in the views of most stakeholders and SPOR has been successful at developing relationships and reaching a broad group of stakeholders across sectors and participant types.

- Peer review processes are strong with the inclusion of patient representatives being a positive and novel approach.

- The extensive and iterative process for Network development and selection has been effective and has continuing effects on even those projects that were not selected for funding (i.e., groups not funded are still working together).

There are six areas in which effectiveness can be improved, including:

- Communications overall require improvement, including the need for further clarification of the mandates for each of the SPOR core elements, communication of support available from the SUPPORT Units, consistent and common definitions of POR and patient engagement (PE), and tailored communications targeted to different stakeholders.

- Most stakeholders identified a level of uncertainty regarding “what’s next,” particularly with respect to the limits of the initial the five-year funding term. This highlights the need for greater communication regarding plans for future funding beyond initial commitments.

- Patient engagement is still a work in progress with enhancements needed to support training and mentoring, as well as determining best practices for engaging patients. This includes strengthening SPOR’s PE core element through increased work on capacity development (CD) (patients learning how to participate in research, and researchers learning how to effectively engage patients) as well as expanding national efforts to support more consistent and well-communicated development of PE and CD.

- There has been a low level of understanding and slow uptake by some areas/members of the research community who are not convinced of the value of POR or PE, mainly related to the lack of hard evidence as to its impact on the quality of research or the importance of the resulting clinical outcomes.

- There is a lack of clarity regarding SPOR’s many elements at both the national and provincial/territorial levels. As a result, the alignment of priorities and activities, how various capabilities and services are to be integrated and leveraged, and how all elements work together going forward could be better defined and are confusing to many participants.

- Performance measurement was consistently identified by stakeholders as needing attention. It is not clear the right things are being measured (i.e., considerable measurement of activities and limited measurement of outcomes) and the collection and reporting of performance data is believed to be quite onerous for funded recipients.

Although SPOR is in its initial phases of implementation, it has advanced toward achievement of its stated immediate outcome areas. The main areas of achievement include:

- SPOR is now committing funding at full scale to its core components and has leveraged partner dollars, meeting is own requirement for 1:1 matching and in most cases exceeding this ratio.

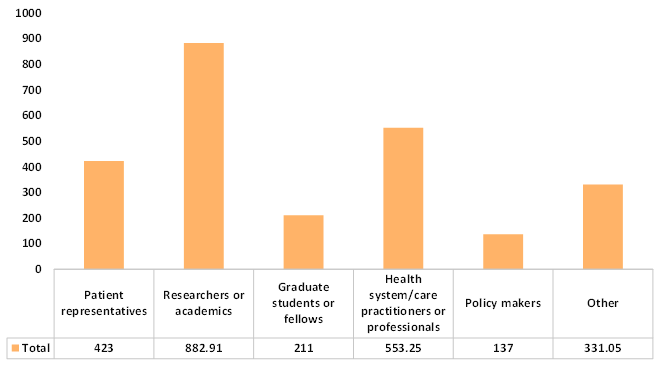

- Six SUPPORT Units have been established, many of which are putting high priority on building data platforms. SUPPORT Units have increased their dataset holdings from 253 to 534 over a two-year period and have collectively provided consultation and research services reaching 1,872 stakeholders.

- Demonstration projects undertaken by the SUPPORT Units are showing early signs of POR research outputs, with examples of success in using Big Data in Newfoundland & Labrador, in engaging patients in Ontario, and in the development of a best practice clinical service protocol in Manitoba.

- The Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre has been operational since early 2014 and has delivered against two of its key objectives with the completion of a model clinical trials agreement and a clinical trials asset map.

- Three national research Network funding opportunities (Mental Health; Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovation, and Chronic Diseases) have been launched, resulting in seven Networks funded.

- SPOR has engaged stakeholders across sectors and across participant communities with extensive efforts at the national and provincial/territorial levels, bringing researchers, clinicians, policy makers and patients together across sectors and geographies.

In terms of progress toward intermediate outcomes, SPOR is early in its influence on the health research landscape and shifting the culture towards POR. The alignment and integration of the activities of SPOR’s core elements, enhanced engagement of patients, stronger communication of key concepts, future plans and priorities, and early wins will help to increase buy-in for POR and support the further implementation and achievement of intended results.

Recommendations

Overall, SPOR is relevant, addresses an ongoing need for POR, and is demonstrating expected performance given the stage of implementation, supporting the need for continued involvement and investment in SPOR by CIHR; however, some improvements are required to further strengthen its design and delivery.

The following recommendations were identified to improve program performance:

- CIHR should increase efforts to strengthen SPOR’s role in a common agenda for change to patient-oriented research.

- CIHR needs to continue to focus on increasing buy-in of POR and changing the culture, identify and communicate best practices in POR and enhance communication to clarify definitions of many POR terms, including POR itself.

- SUPPORT Units need to increase communications and outreach to their broad stakeholder community in relation to SUPPORT Unit services available and initiatives undertaken.

- CIHR should provide strategic guidance regarding how SPOR elements are to work together toward achieving SPOR’s intermediate and long-term outcomes.

- CIHR, in collaboration with its established SPOR governance structures, should enhance guidance on operationalizing SPOR elements, in particular, clarifying how elements are expected to work and coordinate together.

- CIHR should communicate plans for moving beyond the initial five year funding period to manage sustainability expectations for CIHR investments in SPOR.

- CIHR needs to provide clear communications regarding SPOR funding, and options beyond the current five-year funding commitment to some elements.

- CIHR should strengthen approaches to enable cross-learning, sharing of best practices, and collaboration; this should occur within and across SPOR elements and between CIHR and Canadian and international organizations.

- CIHR should re-examine the structure, operations and effectiveness of working groups, and encourage cross-provincial initiatives, particularly among SUPPORT Units.

- CIHR and all SPOR elements should encourage ongoing interaction/connection and relationship building with other POR initiatives.

- CIHR should continue to support effective management and administrative functions within funded SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks and across these elements.

- CIHR should require SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks to be supported by CEO/COO-type management positions, if not already present, to help manage operational obligations, administrative requirements and the high corresponding workloads in these areas.

- CIHR should review the funding model in place, and adjust funding flow based on the stage of development/need of the element.

- CIHR should revise the existing SPOR performance measurement strategy to balance administrative/operational outputs with outcomes/impacts.

- Indicators should be re-oriented from tracking primarily activity-based or output indicators toward outcomes and impacts; consider applying a “collective impact” lens.

- CIHR should improve its financial monitoring and coding for SPOR grants and awards expenditures (including partner contributions) and for operating and maintenance expenditures.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings from the evaluation of the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR). This report includes a summary description of SPOR, the approach and methodology used for completing and analysing the data sources supporting the evaluation, and the presentation of concluding findings from all lines of enquiry. Key findings are drawn against the applicable evaluation questions relating to SPOR’s relevance, design and delivery, and performance.

1.1 SPOR Profile

Patient-oriented research (POR) refers to a continuum of research that engages patientsFootnote 1,Footnote 3 as partners, focusses on patient-centric priorities and improves patient outcomes individually and in communities. This research, conducted by multidisciplinary teams in partnership with relevant stakeholders, aims to apply the knowledge generated to improve healthcare systems and practices.Footnote 4

POR can range from initial studies in humans to comparative effectiveness and outcomes research, and the integration of this research into the health care system and clinical practice. The goal of POR is to better ensure the translation of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the point of care (i.e., to patient diagnoses and treatments), so as to help ensure greater quality, accountability, and accessibility of care. It aims to ensure that “the right patient receives the right clinical intervention at the right time, ultimately leading to better health outcomes.” While clinical research has provided the basis for the development and application of health interventions, comparative evaluations of these interventions have lagged in their ability to provide guidance as to when and for which patients to apply them. Such results in clinical research have led to a push internationally towards POR, which has become a high priority for international peer organizations including those in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.

Various factors in the Canadian environment throughout the turn of the century have added impetus to the need to move forward on the development and implementation of a comprehensive national strategy for POR. First, while investments in health research have led to the development of a vast array of preventive, diagnostic and treatment interventions for health, there has been increasing impatience among clinicians, policy makers and patients with the slow pace at which scientific discovery has resulted in new products or interventions. Second, significant gaps in high quality evidence on comparative effectiveness have shown that it can be difficult to establish guidelines for appropriate care. Third, in tighter economic times, funders of basic biomedical research, including federal and provincial governments and health charities, have been anxious to see and to explain to taxpayers and donors the public benefit of the billions of dollars invested in scientific research.

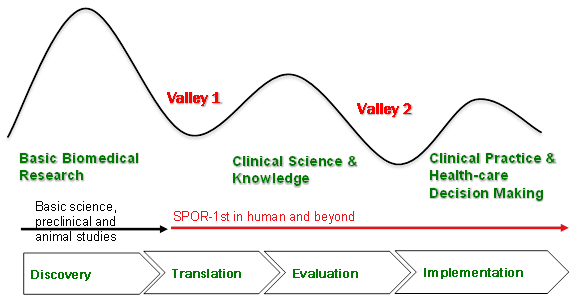

In response to this identified need, Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research was developed to set out a vision about how Canada’s POR model will be designed. SPOR’s Strategy document depicts the Canadian landscape as, in effect, facing a dual challenge in the research-to-practice continuum. The strategy states this often being referred to as the two "Death Valleys". Valley 1 refers to the decreased capacity to translate the results of discoveries generated by basic biomedical research in the laboratory to the bedside or careside as well as to successfully commercialize health discoveries. This negatively impacts Canada's clinical research and knowledge base and its international competitiveness. Valley 2 refers to the limited capacity to synthesize, disseminate and integrate research results more broadly into health care decision-making and clinical practice.Footnote 1

Exhibit 1 – The Two Valleys of the Research-to-Practice Continuum

Low capacity to translate the results of discoveries generated by basic biomedical research in the lab to the bedside as well as to successfully commercialize health discoveries. Bridging Valley 1 by fostering public-private partnerships and by providing clinical validation of research results.

Limited capacity to synthesize, disseminate and integrate research results more broadly into health care decision-making and clinical practice. Bridging Valley 2 by ensuring that research results are integrated into the healthcare system.

Adapted from Steven Reis, University of Pittsburgh and Harold Pincus, Columbia University.

Exhibit 1 long description

Exhibit 1 describes how Canada faces a dual challenge in the research-to-practice continuum, often referred to as the two Valleys. Valley 1 is represented as a dip in a line graph that happens in between basic biomedical research and Clinical Science & Knowledge. This negatively impacts Canada’s clinical science and knowledge base and its international competitiveness. Valley 2 is represented as another dip in a line graph that happens between clinical science and knowledge and clinical practice and health-care decision-making. These two valleys must be bridged if Canada is to bring evidence to bear to enhance health outcomes and ensure a sustainable health care system.

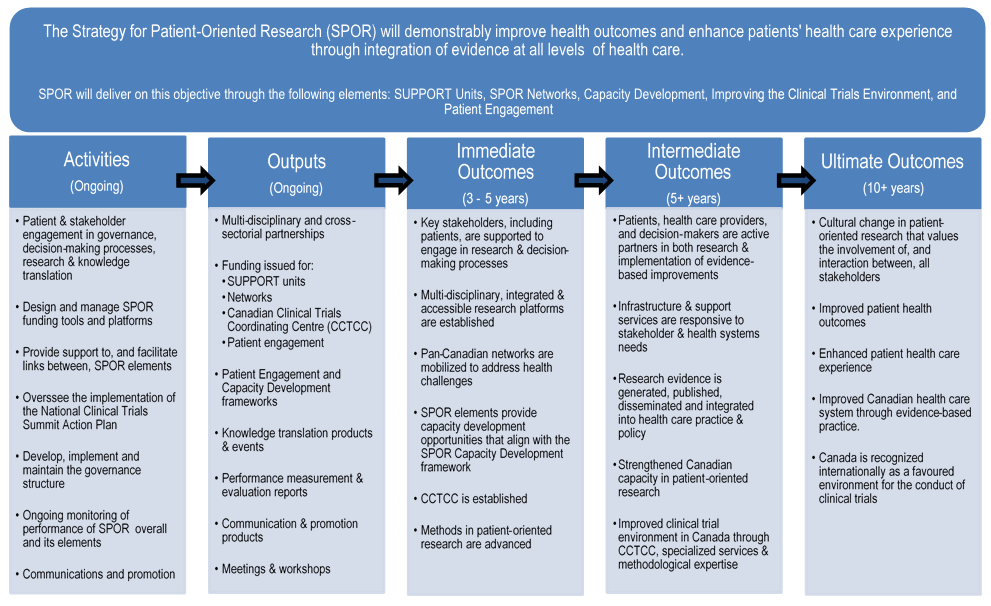

In response to these pressures, SPOR was developed with the vision to demonstrably improve human health outcomes and enhance patients' health care experience through integration of evidence into the health care system and clinical practice. It is expected that through the integration of research evidence into clinical practices, the act of putting patients first would support Canada in ensuring that research will have a greater impact on treatments and services provided in clinics, hospitals and doctors' offices throughout the country.

Chevrons at the bottom of the exhibit represent the research cycle starting with discovery and moving to Translation, Evaluation and Implementation. SPOR begins at the second chevron, Translation. SPOR does not focus on basic biomedical research but on 1st in human studies and beyond.

In response to these pressures, Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research was developed with the vision to demonstrably improve health outcomes and enhance patients' health care experience through integration of evidence into the health care system and clinical practice. SPOR was first announced in August 2011. It is expected that through the integration of research evidence into clinical practices, the act of putting patients first would support Canada in ensuring that research will have a greater impact on treatments and services provided in clinics, hospitals and doctors' offices throughout the country. SPOR represents a shared agenda among federal, provincial and territorial partners dedicated to the integration of research into care.

The immediate and intermediate outcomes defined for SPOR include:

| Immediate Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes |

|---|---|

|

|

An important principle of SPOR is the leveraging of non-federal partner funds to match, at a 1:1 ratio, the investments made from the federal government toward the core elements of SPOR. To date, $357 millionFootnote 5 has been invested or committed by CIHR.

Several additional principles are in place for the federal investments in the core elements of SPORFootnote 6.The principles include:

- Patients need to be involved in all aspects of research to ensure questions and results are relevant and integrated into practice;

- Decision-makers and clinicians need to be involved throughout the entire research process to ensure integration into policy and practice;

- Effective patient-oriented research requires a multi-disciplinary approach;

- SPOR is focused on first-in-human (and beyond) research designed to be transformative in nature and improve patient outcomes and/or the effectiveness and efficiency of the health care system; and,

- SPOR is outcome driven and incorporates performance measurement and evaluation as integral components of the initiative.

1.2 Core Elements of SPOR

SPOR consists of five core elements, with each element having been structured to address specific challenges identified as having delayed or prevented the translation of high quality research to improvements in patient outcomes within Canada. These elements include:

- SUPPORT Units

- SPOR Networks

- Capacity Development (CD)

- Improving the Clinical Trials Environment

- Patient Engagement (PE)

SPOR was initially launched in 2011, with the release of the formal Strategy document. In the five years since that time, each SPOR element has been developed and implementedFootnote 7 within varying timeframes. For the most part, SPOR core elements have been in place for a maximum of two years, with most only being active for one year.

Official program documents indicate there was a planned delay through the first two years of SPOR with activities identified for 2011-12 to include the establishment and engagement of SPOR’s National Steering Committee, the determination of priorities, the creation of the funding opportunities for the Networks and SUPPORT Units, as well as some specified work in the Clinical Trials area.

Additionally, there are a number of relevant and important programs preceding SPOR that helped to set the stage/prime the Canadian clinical and patient-oriented research community for the launch and implementation of SPOR. SPOR has a number of Foundational Investments associated with it (e.g., operating grants, catalyst grants, knowledge synthesis grants. These Foundational Investments are aligned with SPOR; however, may have begun prior to SPOR being announced, maintained during the design and implementation of SPOR, or were sunsetted post-SPOR implementation.

For example, there are a number of Foundational Investments that were, and continue to be, important, as most play a role in the development of SPOR-relevant research capacity and are directly aligned with SPOR. For example:

- One of the stated vision-achieving goals of SPOR is to grow Canada's capacity to attract, train and mentor health care professionals and health researchers, as well as to create sustainable career paths in patient-oriented research. Through the Foundational Investments, CIHR continued to support:

- MD/PhD students through the MD/PhD Program Grants;

- Students pursuing health professional degrees (often at the undergraduate level) to engage in research (usually during the summer) through the Health Professional Student Research Awards program;

- Trainees at the doctoral and post-doctoral level as well as new investigators through priority announcements on the relevant CIHR open award programs in Clinical Research; and

- Mentoring of clinical trial trainees through the Randomized Controlled Trials Mentoring program.

These Foundational Investments are not included in the evaluation’s scope.

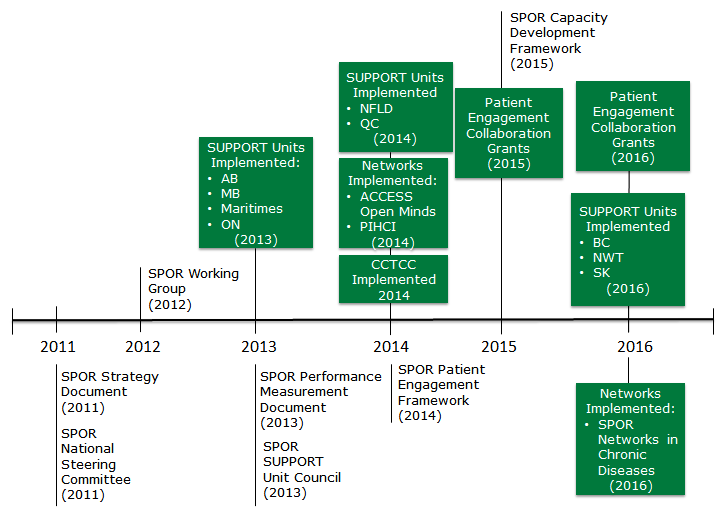

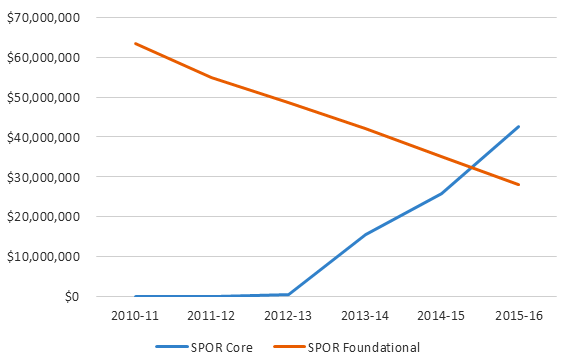

Exhibit 2 depicts the progressive implementation of the core SPOR elements.

Exhibit 2 – Timeline of SPOR Elements and Key Documents since 2011

Exhibit 2 long description

This figure is a timeline of SPOR elements and lay documents since 2011.

SPOR was initially launched in 2011, with the release of the formal Strategy document: Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. The National Steering Committee (NSC) was established also in 2011.

In 2012 the SPOR Working Group was established.

In 2013 the SPOR Performance Measurement Strategy was developed and the SUPPORT Unit Council (SSUC) was established. The first four SUPPORT Units were implemented in Alberta, Manitoba, Maritimes and Ontario.

In 2014 two more SUPPORT Units were implemented in Newfoundland & Labrador and Quebec and two SPOR Networks were launched: ACCESS Open Minds and Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations (PIHCI). Also the Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre (CCTCC) was established and the SPOR Patient Engagement Framework was developed.

In 2015 the SPOR Capacity Development Framework was developed and Patient Engagement Collaboration Grants were initially launched.

In 2016 three more SUPPORT Units were implemented in British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Northwest Territories, the SPOR Network in Chronic Diseases is launched and Patient Engagement Collaboration Grants continue to be offered.

The description and evolution of each core SPOR element is described in the following sections.

1.2.1 SUPPORT Units

Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials (SUPPORT) Units are locally accessible, multidisciplinary groups of specialized research resources, policy knowledge, and patient perspectives. SUPPORT Units have been created to provide support and expertise to those pursuing POR. Additionally, they are tasked with facilitating decision-making within the health services setting, fostering the implementation of best practices, and promoting collaboration among researchers engaged in POR.

SUPPORT Units have been or are being established in collaboration with the provinces and territories, who have a significant role in directing the work they carry out.

The concept of SUPPORT Units was mapped out at a one-day meeting in March 2011 that included researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and CIHR representatives. In 2012, CIHR made available to all provinces/territories, a funding opportunity that outlined a set of instructions to assist with the development of jurisdictional SUPPORT Unit business plans. The first SUPPORT Units were approved for funding in 2013 and spent much of that year finalizing strategies and work plans.

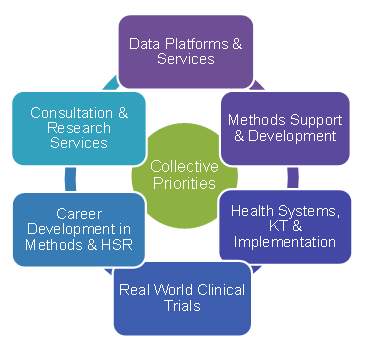

Each SUPPORT Unit has committed to the following six key components (these are CIHR requirements):

- Data Platforms and Service that enhance access to large administrative data sets, train and provide data analysts to respond to requests for de-identified data, provide a central platform for primary data collection (Alberta), and provide data ambassadors to deal with data sharing agreements, privacy, ethics and consent.

- Methods Support and Development that enhance access to expertise such as biostatistics, epidemiology, clinical trial design, survey methods and health economics.

- Health Systems Research, Implementation Research and Knowledge Translation which include activities that put knowledge to action, enhancing uptake.

- Pragmatic Clinical Trials that support common services such as ethics review and streamlined legal services.

- Career Development in Methods and Health Services Research that offer capacity building in health services research fields (e.g., biostatisticians, health economics) through academia, mentorship and leadership supports.

- Consultation and Research Services which provide service support to researchers in areas such as methodological development, administrative needs, project management, and data management.

Each SUPPORT Unit must also undertake a demonstration project or projects. These are meant to show the benefits of POR, and demonstrate quickly that the POR model can work.

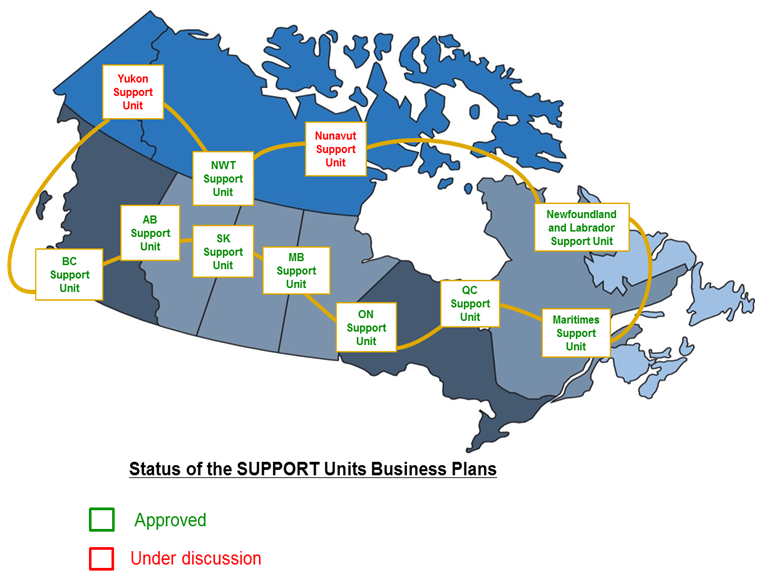

To date, CIHR has invested $68MFootnote 8 in SUPPORT Units (Alberta, Manitoba, Maritimes, Ontario, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Quebec) and will invest $127MFootnote 9 over the next five years to roll out the remaining SUPPORT Units (British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and three territories). The implementation stage of the SUPPORT Units as of February 2016 is:

- SUPPORT Units implemented:

- 2013: Alberta, Manitoba, Maritimes, Ontario

- 2014: Newfoundland & Labrador, Quebec

- SUPPORT Units approved and moving towards implementation:

- 2015-16: British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Northwest Territories

- SUPPORT Units in ongoing discussions:

- Yukon and Nunavut.

A SUPPORT Unit Council (SSUC) was established in 2013. The mandate of the SSUC is to provide an opportunity for information sharing and collaboration among SUPPORT Units throughout the development and implementation of this element of SPOR. It does not have powers to compel actions.

The SSUC is comprised of two co-chairs, one from CIHR and one from the SUPPORT Units, one lead person from each SUPPORT Unit and two other members from CIHR. The SSUC Terms of Reference identifies they have been meeting four to five times per year.

The SSUC focuses its attention on the following:

- Sharing information, best practices, tools and lessons learned;

- Advocating for the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research;

- Directing communications between SPOR partners and SUPPORT Unit stakeholders;

- Serving as a sounding board for CIHR and other SPOR partners for new initiatives;

- Coordinating SUPPORT Unit responses to multi-jurisdictional issues arising when interacting with SPOR Networks; and

- Directing the work of the SSUC working groupsFootnote 10.

SSUC Working Groups (WGs) were formed in 2014 and 2015 to address issues of common interest and are designed to focus on a particular issue. The WGs report to the SSUC and have been established as follows:

- Performance Measurement Working Group (2014);

- Knowledge Translation Working Group (2014);

- CD Working Group (2015);

- PE Working Group (2014); and

- Data Working Group (2015).

1.2.2 SPOR Networks

SPOR Networks are national collaborative research networks involving the full range of SPOR stakeholders (patients, health professionals, decision makers, health researchers and other stakeholders). They focus on specific health challenges identified as priorities in multiple provinces and territories. They are intended to pursue research and generate evidence and innovations designed to improve patient health and health care systems.

In January 2011, CIHR hosted a round-table meeting to discuss the vision for the pan-Canadian Networks. The meeting’s goal was to determine how Canadian clinical research networks should be best organized, governed, and resourced. The specific goals of the roundtable were:

- To understand what constituted a Canadian Patient-Oriented Research Network and how it might best function.

- To share best practices and realities in developing and running national research networks.

- To provide CIHR with guidance on the development and implementation of future Canadian Patient-Oriented Research Networks and information needed to develop funding opportunities related to them.

Through the SPOR development process, CIHR solicited stakeholder input on research areas of greatest need. Based on the input received, the SPOR National Steering Committee (NSC) then helped to refine the areas in which SPOR funding should be targeted for the creation of Networks.

The application process has been different for each of the Networks. The process may include a combination of the following: expressions of interest, letters of intent, strengthening workshops and full applications. The purposes of the strengthening workshops are to strengthen applications and facilitate dialogue between applicants, potentially identifying synergies among applicants. In some instances, funding is allocated to applicants through the letter of intent stage to facilitate development of the full application.

To date, seven networksFootnote 11 in three different areas, described below, are being implemented to deliver on the SPOR objectives. These networks are pan-Canadian initiatives.

From 2010-11 to 2020-21, CIHR has committed $83.2 for Networks, of which $12.6M had been spent during the timeframe of the evaluation (2010-11 to 2015-16).

SPOR Network in Youth and Adolescent Mental Health – ACCESS Open Minds

The SPOR Network in Youth and Adolescent Mental Health, with delivery through ACCESS Open MindsFootnote 12, aims to bring about transformational change in addressing adolescent and youth mental health and well-being. The Network seeks to improve the care provided to young Canadians with mental illness through assisting in connecting patients and youth with researchers, health care professionals, and decision-makers in order to foster the translation of research findings into practice and policy.

The funding opportunity for the Youth and Adolescent Mental Health Network was launched in January 2013. In June 2014, the ACCESS Open Minds Canada research network for youth and adolescent mental health was announced. The Network is a collaborative effort between CIHR and the Graham Boeckh Foundation.

Pan-Canadian SPOR Network in Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations (PIHCI)

In November 2013, the funding opportunity for the Primary Integrated Health Care Innovations (PIHCI) Network was launched. PIHCI entered Phase I implementation in 2014. Phase 2 of PIHCI proceeded through 2015 with Quick Strike research projectsFootnote 13 and applications for full membership in the pan-Canadian Network.

This pan-Canadian Network (a network of networks) is intended to support an alliance between research, policy and practice to create responsive learning networks. It is intended to deal with delivery of care both within and across sectors of health care (e.g., public health, home and community care, primary, secondary, and tertiary care) and outside the health sector (e.g., education, social services).

PIHCI is a key CIHR initiative under SPOR and also the Community-Based Primary Health Care Signature Initiative (CBPHC). A core requirement for PIHCI Network membership necessitates members to link with CBPHC Innovation Teams in a member’s jurisdiction.

SPOR Networks in Chronic Disease

In October 2014, the funding opportunity for the Networks in Chronic Diseases was launched. The focus of these networks is on the translation of existing and new knowledge generated by basic biomedical, clinical, and population health research into testing of innovations that can improve clinical science and practice and foster policy changes, leading to transformative and measureable improvements in patient health outcomes, and in efficient and effective healthcare delivery within five years.

Applications were submitted in early October 2015, with results released in late February 2016. Five networks were funded in March 2016. As these networks were in the applications phase at the time of this evaluation, they were purposely excluded from the evaluation scope.

1.2.3 Capacity Development

Capacity development is intended to grow, support and sustain the capacity for a collaborative, interdisciplinary and innovative patient-oriented research environment capable of addressing evolving health care questions, contributing to enhancing patients' health care experience and improving health outcomes.

In August 2012, an External Advisory Committee (EAC) was mandated to develop a report identifying the deficiencies in patient-oriented research within Canada. In 2013, a national workshop was held to collect feedback on barriers to patient-oriented research. The EAC drafted guiding principles and suggestions for implementation and released its report “Training and Career Development in Patient-Oriented Research” in June of 2013. Further consultation with SPOR stakeholders including those that are involved directly in building capacity in a variety of sectors took place through a workshop on capacity development in March 2014, with a final CD Framework being released in August 2015.

The SPOR CD FrameworkFootnote 14 was designed to encourage a shared vision, key principles, and considerations for capacity development in POR. In alignment with this framework, training, mentoring, and career support is to be integrated into the SPOR Networks and SUPPORT Units, with each Network and SUPPORT Unit being required to articulate a training and capacity development strategy.

1.2.4 Clinical Trials

An important goal of SPOR is to strengthen organizational, regulatory, and financial support for clinical trials in Canada and enhance patient and clinician engagement in these studies. Implementing and funding multi-centre clinical trials is difficult in the current Canadian context, and Canada is perceived to be losing its competitive edge. To improve Canada's competitiveness in conducting clinical trials, SPOR has developed this element, which is designed to help overcome a number of identified barriers. The first ever Canadian Clinical Trials Summit was held on September 15, 2011 in partnership by CIHR, HealthCareCAN (formerly the Association of Canadian Academic Healthcare Organizations), and Innovative Medicines Canada (formerly Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (Rx&D)). The purpose of the Summit was to include various public, private and academic participants in the development of an action plan to “further guide academia and clinical sites, government, and industry on a common path” in order to “help Canada regain its capacity to attract clinical trials.” The first recommendation of the Action Plan called for the development of “a national headquarters for clinical trials improvement activities”. The Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre (CCTCC) was subsequently established through a joint public, private, and academic partnership between CIHR, Innovative Medicines Canada, and HealthCareCAN in 2014. The CCTCC is working to implement the recommendations from the 2011 Clinical Trials Summit Action PlanFootnote 15, which were to:

- Establish implementation and coordination headquarters and resources;

- Measure, monitor, manage, and market clinical trial performance improvements;

- Integrate health system and research infrastructure to ensure quality and sustainability;

- Improve efficiencies of ethics reviews and advance strategic issues;

- Develop a database of registries and consider a national patient recruitment strategy;

- Adopt common Standard Operating Procedures, training and certification;

- Improve and use the common clinical trials contract;

- Optimize intellectual property protection policy, scientific research and experimental development tax credits; and

- Signal Canada’s interest globally.

Additionally, the clinical trials element is incorporated as a core function of each provincial/territorial SUPPORT Unit, as well as through the clinical trials activities conducted across the SPOR Networks, and through the engagement of clinicians and clinical researchers across the SPOR governance and reporting structures.

1.2.5 Patient Engagement (PE)

By encouraging a diversity of patients to tell their stories, new themes may emerge to guide research. Patients are expected to gain many benefits through their involvement in research, including increased confidence and mastery of new skills, access to information they can understand and use, and a feeling of accomplishment from contributing to research relevant to their needs.

A key objective of Canada's SPOR is for patients, researchers, health care providers, and decision-makers to actively collaborate to build a sustainable, accessible and equitable health care system. Experience has shown that the priorities of clinical researchers and healthcare systems may not always perfectly match the priorities, concerns, and needs of patients.

Engaging patients is therefore a vital element to be integrated with the development and implementation of all elements of SPOR, such as SUPPORT UnitsFootnote 16 and Networks. There is also activity in sharing knowledge on PE across SPOR elements. For example, the SUPPORT Units are noted to be actively sharing and involved in CIHR-sponsored workshops on the topic.

In response to feedback regarding the need to clarify SPOR’s approach to PE from a variety of sources, including the research community, SPOR's National Steering Committee requested the development of a PE Framework. The PE Framework has been designed to establish key concepts, principles, and opportunities for PE in identifying health research priorities and in designing and conducting research projects.

In January 2014 and the spring of 2014, CIHR hosted a workshop and consultations to develop the SPOR PE Framework. This Framework was published and disseminated to stakeholders in June 2014.

The SPOR PE FrameworkFootnote 17 elaborates on what patients contribute to the research process and why it is needed:

“Patients bring the perspective as "experts" from their unique experience and knowledge gained through living with a condition or illness, as well as their experiences with treatments and the health care system. Involvement of patients in research increases its quality and, as health care providers utilize research evidence in their practice, increases the quality of care.

Engaging patients in health care research makes (investments in) research more accountable and transparent, provides new insights that could lead to innovative discoveries, and ensures that research is relevant to patients concerns. The international experience with engaging citizens and patients in research has shown that involving them early in the design of studies, ideally as early as at the planning stage, leads to better results."Footnote 18

As a partner in SPOR and seeking to align itself with the SPOR PE Framework, CIHR developed a citizen and patient engagement (CPE) implementation strategy with a number of cross-cutting components, some with direct implications for SPOR. These particular components are also at various stages of implementation:

Examples of further work by CIHR include:

- Patient Engagement Collaboration Grants: 11 projects were funded (as of March 31, 2016) with objectives to: identify and implement inclusive engagement mechanisms, processes and approaches that value patient perspectives, experiences and skills throughout the research process; and facilitate opportunities for researchers and knowledge users, including patients, to work together to identify problems and gaps, set priorities for research, and produce and implement solutions. At the time the evaluation was designed, these grants had been funded for less than six months and so were excluded from the scope of this evaluation.

- The Foundational Curriculum for Patient-Oriented Research: Development of a resource to build capacity for all who are engaged in patient-oriented research (prepare citizens and patients to be active partners). The curriculum modules use a co-learning approach to foster collaborations between researchers and patients. CIHR intends to work collaboratively to situate this curriculum within a broader system of learning, and co-development of content is to take place. Ultimately, the curriculum will be rolled out nationally and eventually be made open access.

1.3 Target Populations

All Canadians are expected to benefit from SPOR, as it is hoped to lead to:

- improved health for Canadians by helping to ensure that the best research evidence moves into practice, enhancing the health care experience for patients and improving health outcomes for Canadians;

- economic benefits by optimizing spending on health care systems, reinvesting resources where the evidence shows greatest impact, and attracting private investments in evaluative research;

- innovation in patient-centred care in areas such as e-health, implementation science, and clinical practice;

- more clinical research by improving the environment for clinical trials in Canada; and

- collaboration among provinces and territories by providing jurisdictions with opportunities to learn from each other, translating best practices in patient-oriented care across Canada.

The patient should benefit from SPOR through receiving the right care in the right place at the right time. Patient-oriented researchers should benefit from training, research support services and an improved environment for clinical research. Health care professionals and policy makers should benefit from the timely and efficient translation of research innovations from the research setting to patient care settings, as well as the evaluation and synthesis of existing knowledge and its proper transfer to the clinical setting. Finally, the provincial governments and health care administrators should benefit from a more cost-effective, efficient, and affordable health care system.

1.4 Stakeholders

SPOR maintains a broad range of stakeholders, involved and interested in the development and implementation of its objectives including:

| Federal Departments | Provincial and Territorial Governments and Funding Agencies | National Partners and Stakeholders | International Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

Other federal departments with an interest in issues relevant to SPOR may be consulted by SPOR where appropriate. These include:

|

SPOR partners maintain linkages with provincial and territorial governments, primarily through the following mechanisms which have responsibilities to address health issues:

|

SPOR maintains linkages with many players concerned with POR, including patients and caregivers, health charities and other not-for-profit organizations, researchers, academic institutions, health practitioners, health organizations, and the pharmaceutical sector. Some examples include the following:

|

SPOR maintains linkages with several international organizations, which include:

|

1.5 Governance

The governance structure of SPOR consists of a National Steering Committee and a CIHR SPOR Working Group. The governance structure is supported by the Priority-Driven Research Branch within the Research, Knowledge Translation and Ethics (RKTE) Portfolio of CIHR. In addition, each SUPPORT Unit and SPOR Network is required to have a governance structure, which includes appropriate mechanisms for PE.

SPOR National Steering Committee

The National Steering Committee (NSC) was established in 2011 and oversees SPOR development and implementation.

The committee is co-chaired by the Deputy Minister of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care and the President of CIHR. Members include patients, federal/provincial/territorial governments, provincial health research funders, academic institutions, health care organizations, researchers, health charities and industry. The National Steering Committee’s composition also respects a nationwide geographical representation. CIHR provides secretariat services for the Committee.

SPOR Working Group

The SPOR Working Group was established in 2012 and provides scientific leadership within CIHR for the development, implementation and co-ordination of CIHR’s activities and initiatives related to SPOR. The Working Group also provides on-going monitoring and identifies refinement of activities and initiatives, as needed. Ad-hoc external advisory committees are engaged for advice on various specific issues as necessary.

The Working Group is chaired by the Chief Scientific Officer of CIHR, and consists of five Institute Scientific Directors, each being a champion of one of the five SPOR elements. It also includes the Associate VP Research, Knowledge Translation and Ethics, the Director General of Priority-Driven Research Branch, and Manager of Major Initiatives.

1.6 CIHR Institute Involvement in SPOR

CIHR integrates research through a unique interdisciplinary structure made up of 13 "virtual" institutes. Each Institute is dedicated to a specific area of focus, linking and supporting researchers pursuing common goals. All CIHR Institutes are engaged in SPOR, though to varying degrees. Institute engagement with SPOR can be characterized in the following ways, which are not mutually exclusive (see Appendix B for details):

- Providing scientific leadership (e.g., serving as a Champion for a SPOR element; co-leadership for designing SPOR Networks; presentations to SPOR governance structures; shaping scientific content of SPOR funding opportunities; contributing to the development of performance measurement frameworks).

- Serving on SPOR governance structures (e.g., SPOR Working Group) or consulting Institute governance structures (e.g., Institute Advisory Boards on SPOR elements or SPOR overall).

- Making financial contributions from Institute Strategic Initiative budgets (e.g., to Network development grant funding opportunities) or Institute Support Grant budgets (e.g., funding strengthening workshops).

- Ensuring strategic linkages to other Institute priorities (e.g., linking SPOR to other Institute strategic priorities or ensuring alignment where possible) or stakeholders (e.g., partnership development).

1.7 Resources

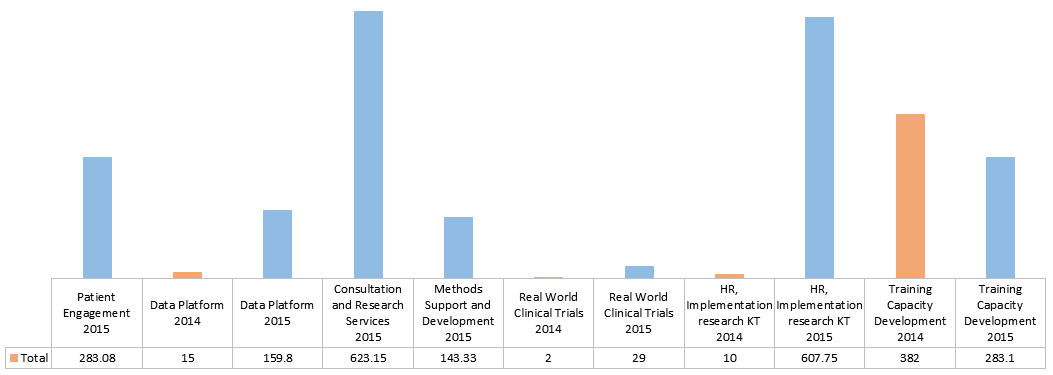

An overview of CIHR grants and awards expenditures on SPOR over the evaluation timeframe is provided in the table below:

| 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $63,561,791 | $54,927,762 | $49,018,043 | $57,581,279 | $61,022,134 | $70,729,241 | $356,840,250 |

*Summary of figures provided by CIHR current as of March 21, 2016.

1.8 Evaluation Purpose and Scope

SPOR is a complex and complicated program and reflects a large system of stakeholders, delivery partners, activities, and linkages to other programming efforts both within CIHR and in the provinces and territories. Although many of the SPOR partners were engaged in the evaluation through interviews, the evaluation was of CIHR’s contribution to SPOR core elements only.

The SPOR evaluation covers the five-year period 2010-11 to 2015-16 and was scoped to cover issues of relevance, design and delivery, and performance. The purpose of the evaluation is twofold:

- To meet the CIHR’s accountability requirements as a federal government agency (Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation and Financial Administration Act).

- To provide an independent and objective assessment of the implementation and performance of SPOR to date to inform program decision-making.

In order to prioritize the focus on the implementation of the core elements and assess progress toward immediate outcomes as outlined in the SPOR performance measurement strategy, the following calibration considerations were made:

- Scope and resources for the evaluation were designed to complete the evaluation in eight months.

- The evaluation was designed to meet information needs of the program through the assessment of the implementation of SPOR core elements, especially the SUPPORT Units, and to inform senior management on progress to date, course corrections needed, and evidence of early/quick wins.

- The evaluation aligned with TBS requirements to demonstrate impact from funds secured through TB submissions which are mapped to the Performance Measurement Strategy submitted to TBS.

Given these scoping considerations, the evaluation focused on the deployment of SPOR core elements and short-term progress towards objectives, and used the program profile contained in the SPOR Performance Measurement Strategy as the baseline implementation plan.

The focus on Foundational Investments was limited to outlining the investments made through the evolution of SPOR from 2010-11 to 2015-16 as well as considering these investments in the assessment of efficiency under the performance issue. In terms of assessing the outcomes of the Foundation Investments, these were scoped out given they were not deliberately designed at the outset to achieve SPOR outcomes as stated in the logic model, resources to assess the investments were not available, and some of the investments were in the scope of previous, ongoing (e.g., scholarships) and planned (e.g., operating support) evaluative activities.

The scope of the evaluation is summarized in the following table:

| The evaluation covers: | The evaluation does not cover: |

|---|---|

|

|

Further elaboration of some of the components excluded from the evaluation scope can be found in section 2.3 on study limitations.

1.9 Evaluation Questions

A set of evaluation questions were prepared and vetted by CIHR. The following seven questions were addressed in the evaluation:

SPOR Evaluation Issues and Questions

Relevance

- To what extent does the research funded under SPOR address the need for evidence-informed health care?

- To what extent is SPOR aligned with federal roles and responsibilities?

- To what extent is SPOR aligned with federal government and CIHR priorities?

Design and Delivery

- To what extent has SPOR been implemented as planned?

Performance

- To what extent has SPOR made progress toward the achievement of expected immediate outcomes?

- To what extent has SPOR made progress toward the achievement of expected intermediate outcomes?

- To what extent is SPOR being delivered in a cost-efficient manner?

1.10 Report Structure

The findings and analysis for each of the seven evaluation questions are provided in the following sections of this report. Each section defines the specific evaluation question(s), summarizes the key findings against each of the issue areas, provides details on the analysis and evidence and provides supporting conclusions. There is a final chapter on recommendations for improvement.

2. Methodology

To provide cross-cutting representation and feedback from the various stakeholders involved in SPOR, the evaluation was designed to use multiple lines of evidence. With a very complex program design and implementation that is early in its lifecycle, along with variations by jurisdiction and degrees of progress, the evaluation design relied heavily on interview and case study techniques. Overall, the methodology included the following data sources:

- Document and data review.

- Key informant (KI) interviews.

- Case studies that incorporate:

- Document review, and

- Interviews.

- Governance and administrative structures network analysis.

- A comparative review of three somewhat similar international POR initiatives.

The data sources have been mapped to each of the evaluation issues in the following table:

| Data Sources | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document Review | Performance Data Review | Key Informant Interviews | Case Studies | Governance and Admin Network Analysis | International Comparative Review | |

| Relevance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Design and Delivery | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Performance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

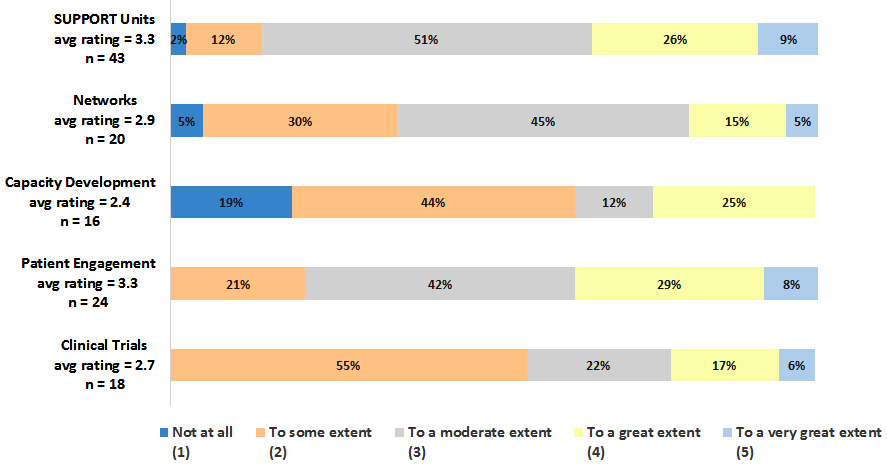

Each of the data sources are described in the sections following and the supporting instruments are provided in the appendices to this report. The number of people interviewed for the key informant interviews and the number of people interviewed for the case studies are presented collectively in the following Exhibits 3 (by method) and 4 (geographically).

Exhibit 3 – Evaluation Response Rates by Method

| Method | Total |

|---|---|

| Case Studies | |

| Capacity Development | 2 |

| Clinical Trials | 4 |

| Networks | 6 |

| Patient Engagement | 10 |

| SUPPORT Units | 68 |

| International KI Interviews | 3 |

| Key Informants | 15 |

| Grand Total | 108 |

Exhibit 4 – Evaluation Response Rate by Geography

| Jurisdiction | Total |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 11 |

| British Columbia | 6 |

| Manitoba | 14 |

| Maritimes | 19 |

| NL & Labrador | 11 |

| Nunavut | 1 |

| NWT | 1 |

| Ontario | 25 |

| Quebec | 14 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 |

| Yukon | 1 |

| International | 3 |

| Grand Total | 108 |

2.1 Data Sources

2.1.1 Document Review

Approximately 40 documents were reviewed, mainly in support of the evaluation questions related to relevance. These included CIHR strategic documents (such as its annual reports and the SPOR overarching strategy document), federal and provincial level strategic documents and reports, industry evaluations, SPOR element specific reporting and other grey literature. The document review was also used to form the contextual description of SPOR utilizing early planning documents to report on the background and vision of the strategy.

2.1.2 Performance Data Review

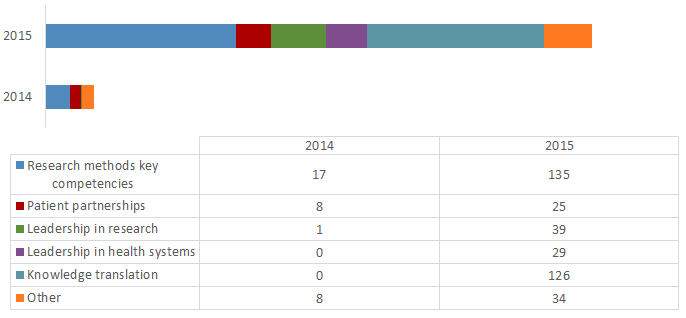

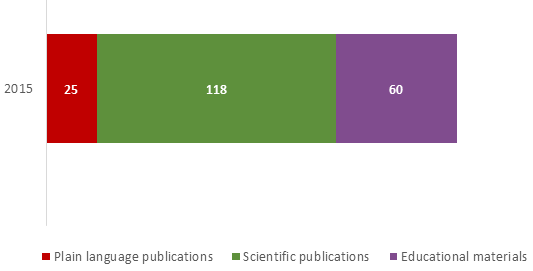

The evaluation compiled a summary of activity data presented in the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 SUPPORT Unit Annual Performance Reports as well as the 2014-2015 Annual Performance Report pertaining to the ACCESS Open Minds Network. This was the entire scope of performance reporting available during the evaluation timeframe. The performance data selected for presentation in this report aligns to the performance indicators as identified in SPOR’s performance measurement strategy. The data is reported at an aggregate level representative of SUPPORT Unit activities collectively. The data presented in this report has not been validated by KPMG and is presented as submitted to CIHR by the provincial SUPPORT Units and the ACCESS Open Minds network.

2.1.3 Key Informant Interviews

A key informant interview sample of 19 individuals was developed that included representatives from CIHR management as well as a sample of SPOR partners, stakeholders and users as part of the evaluation work. The sample was purposefully selected to include individuals with broad knowledge of SPOR. Considerations for interviewee selection included knowledge across all SPOR elements as well as (to the extent possible) other factors such as the academic/institutional/healthcare/patient involvement dimensions, and provincial/territorial representation. The sample of 19 individuals was identified by SPOR program personnel. Fifteen interviewees participated out of the sample (15/19=80% response rate).

2.1.4 Case Studies

Five case studies were developed that focused on the implementation of the five core elements of SPOR in a cross-cutting way against all of the SPOR programming. Two sets of questions were addressed with case study interviewees. The first set of questions related to the specific core element of SPOR being studied and the second set of questions related to the overall strategy of SPOR. The five cases conducted, ordered alphabetically, include:

- Capacity Development: A sample of seven interviewees were identified by SPOR program personnel that included members of SUPPORT Units, as well as members of the External Advisory Committee. This sample was purposefully selected to include individuals with specific knowledge of CD. Two interviewees participated out of the sample (2/7=29% response rate).

- Clinical Trials: An initial interview sample made up of five individuals was developed to include representatives of the Clinical Trials National Advisory Group including public, private, and academic sectors. This sample was later expanded to a total of seven individuals, including representation of the CCTCC Executive Committee as well as additional clinical trials researchers. The sample was purposefully selected to include individuals with specific knowledge on clinical trials. The sample of five individuals was identified by SPOR program personnel, with the two additional personnel being recommended through the interview process. Four interviewees participated out of the sample (4/7=57% response rate).

- Patient Engagement: The scope of the PE case study centred on CIHR’s efforts at a national level in development of the PE Framework as well as PE activities undertaken or connected to the other SPOR elements. A sample of 13 interviewees were identified by SPOR program personnel, including patient representatives, on the basis of their involvement in PE (e.g., through CIHR’s curriculum development and collaboration grants), patient representatives from SUPPORT Units and Networks, and CIHR personnel. This sample was purposefully selected to include individuals with specific knowledge of PE. Ten interviewees participated out of the sample (10/13=77%).

- SPOR Networks: Two Networks were included in the scope of the case study: ACCESS Open Minds and PIHCI. It was considered too early to conduct interviews with direct network participants for the SPOR Networks in Chronic Diseases, since this network was still in the competition process in the fall of 2015. Interview and survey data collection thus focused exclusively on ACCESS Open Minds and PIHCI.

- A sample of seven interviewees for the Networks case study was selected with six interviewees participating (6/7=86% response rate). Although interviews were initially planned with one PIHCI representative from each of three areas (research, policy, clinical), this data collection activity was subsequently expanded to target all PIHCI Interim Leadership Council members through an email survey rather than the individual interviews, with notification given to the Interim Leadership Council during a meeting on October 19, 2015. Note that a more restricted set of questions was asked in the PIHCI survey than during the full interviews. The survey response rate was low at 19% (or 6 out of 32).

- SUPPORT Units: A sample of 54 interviewees for the SUPPORT Unit case study was selected. The sample reflected the Executive Director (ED) and component leads within each SUPPORT Unit, clinicians and/or scientists (usually those involved in one or more of the SUPPORT Unit’s demonstration projects), and representatives of provincial/territorial funding agencies. Some interviews were conducted with individual respondents, although, where possible, interviews were conducted in group fashion with similar respondents from similar groups (i.e., a given SUPPORT Unit’s Executive Director and component leads were, when possible, all interviewed together). A total of 68 interviewees participated, surpassing the selected sample and providing a 125% completion rate for the target interviews. The increase in number of participants is partly due to a snowball effect in the group interviews, where additional people may have been invited to attend, or could not attend but were suggested as important respondents, as well as additional partner interviews being conducted.

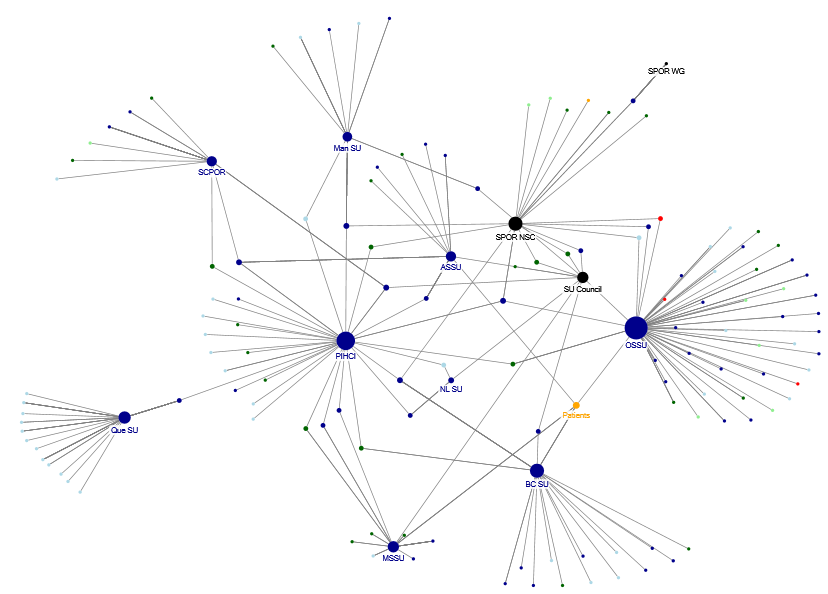

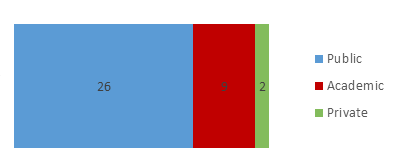

2.1.5 Governance and Administrative Network Analysis

The governance and administrative network analysis was employed as a minor supporting method in the evaluation. Data were collected for each SPOR component having information available through a public internet site. Data were collected for each SUPPORT Unit and the SPOR National Steering Committee in this manner. Contact lists provided from the SPOR program in support of the evaluation were also used to compile data for the PIHCI network, SPOR SUPPORT Unit Council and CIHR’s internal SPOR Working Group.

Web sites were mined for all information related to each component’s governance structure. This included governance, management, and advisory committees. A total of 296 data points were used in the network analysis.

The data elements collected to form the initial edge listFootnote 19 included the person’s name, the organization with which they were associated, the SPOR element with which they were associated, their province/territory, role, and the part of the governance or corporate/administrative structure to which they belonged.

This data were then cleaned and standardized before importing to two separate social network analysis software packages. Two packages were used to obtain the graphical functionality and the mathematical processing functionality required for analysis and presentation. Data were imported at the organizational level, not at the level of each individual. For example:

If the following ties were identified:

- John Smith, University of Alberta, connected to the SPOR National Steering Committee (NSC)

- Harvey Beam, University of Alberta, connected to the Alberta SUPPORT Unit

The following data were imported:

- University of Alberta - SPOR NSC

- University of Alberta - Alberta SUPPORT Unit

A tie represents a connection from one organization to another. The ties in this example are between the University of Alberta and the SPOR NSC and the University of Alberta and the Alberta SUPPORT Unit.

NodeXLFootnote 20 was used to create the network graphs and assemble groups based on the network attributes of “province/territory” and “role”. UCiNETFootnote 21 was used for the mathematical calculations and analysis of degree centralityFootnote 22 and betweennessFootnote 23.

Typical terminology found in social network analysis has purposely not been used (to the extent possible) in this report for ease of portraying the information to readers unfamiliar with the methodology or network theory.

2.1.6 International Comparative Review

The international comparative review was undertaken to explore how other countries are approaching POR initiatives with similar objectives to SPOR. The objective of the review was to gather information on the relative merits of other approaches and models and to obtain perspectives on the pros and cons of the SPOR model versus others. A direct comparison with other initiatives was not undertaken due to the uniqueness of SPOR (large and nationally based).

Through scoping interviews, three initiatives from two organizations were mentioned most frequently as being of most interest to SPOR. These organizations were selected for their experience in POR. The two main international comparison organizations which were reviewed are: The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) in the US and the UK’s National Institute for Health Research with two initiatives: INVOLVE and the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC).

The comparative review was conducted in two stages. First the websites for each of the three initiatives were mined for descriptive information on the models/approaches employed. This was followed by interviews with one representative from each of the initiatives. The contacts for PCORI and INVOLVE were identified through the SPOR program. The SPOR program could not identify contacts for the CLAHRC so respondents were identified through the interviews conducted with key informants and case studies. The main purpose of the interviews was to obtain opinions on SPOR’s key strengths and weaknesses as compared to a respondent’s patient-oriented initiative and to identify lessons learned through their experience in implementation and delivery.

2.1.7 Cost efficiency analysis

By assessing not only a program's relevance and performance, but also the resources the program uses, value for money can be determined.

For the SPOR evaluation, both allocative and operational efficiency were examined in order to determine: (a) whether resources requested from TBS were spent on the activities for which they were requested; and (b) whether this spending occurred at the level and in the timeframe for which it was requested. Resources are considered in relation to the outputs or outcomes achieved, respectively.

The SPOR evaluation was designed to focus only on the SPOR core elements – SUPPORT Units, Networks, CD, PE and Clinical Trials. “Foundational Investments” as well as other investments that are part of SPOR (e.g., Studentships; Fellowships, Clinical Trials funding) were excluded from the evaluation of effectiveness and relevance due to feasibility (available budget, timeframe of evaluation vis a vis funding flow) and direct and deliberate relevance of the timing of these investments relative to SPOR. In many cases, the Foundational investments were well-alignedFootnote 24 with SPOR, however may have begun prior to SPOR being announced, maintained during the implementation of SPOR, or had sunsetted post-SPOR implementation (e.g., operating grants, catalyst grants, knowledge synthesis grants). However these investments are included in the cost-efficiency analysis to help ensure a complete accounting of resources used to deliver on SPOR.

Allocative and Operational Efficiency

Data for the cost-efficiency analyses were provided from CIHR’s Finance and Administration Branch, and Performance Measurement, Reporting, and Data Unit and confirmed with the SPOR Program Manager and staff. These data were examined in relation to the Treasury Board submissions for SPOR over the same period of time. Data for the cost-efficiency analysis included:

- All grants and awards expenditures by CIHR from 2010-11 to 2015-16 (the evaluation time frame) related to the SPOR Elements (SUPPORT Units, Networks, CD, PE, and Clinical Trials) and the Foundational Investments.

- All direct and indirect administration costs for Operations and Maintenance (O&M) as follows:

- Direct salary costs: As SPOR has been ramping up since the first Treasury Board submission in 2010-11, the FTEs dedicated to SPOR, as obtained and reported to TBS since then, was used as the base to calculate the direct salary. CIHR continuously increased the number of FTEs dedicated to SPOR as follows: CIHR obtained three FTEs in the first submission (2010-11), four in 2011-12, four in 2012-13 and 4 in 2013-14 (at which time CIHR noted to TBS that it would fund 5.75 additional FTEs from non-salary funding received). As a result, direct salary costs increased from 2010-11 to reach the steady state of 20.75 FTEs since 2013-14.

- Direct operations and maintenance costs, including: travel and other related expenses for SPOR meetings, such as peer review meetings and the SPOR Summit (e.g., meals, accommodations, space), equipment, training and conference fees for SPOR staff.

- Internal services (indirect costs): As a result of the CIHR exercise completed in November 2015 to calculate CIHR’s Internal Services allocation in compliance with TBS’s Guide on Internal Services, it was determined that CIHR spends $0.03 on internal services for each G&A dollar. This methodology was applied to the total G&A disbursed (new and ongoing, including the Foundational Investments) in the year. For CIHR, such internal services include: Corporate and Governmental Affairs, Communication and Public Outreach, Senior Executive offices, and staff from the Resource Planning and Management Portfolio (e.g., Finance, HR, IT, and Evaluation).

- For direct salary and internal services, employee benefit plan (EBP) costs calculated at the Treasury Board rate of 20 per cent of total salary costs.

- For direct salary and internal services, accommodation costs calculated at the Treasury Board rate of 13 per cent of total salary costs.

A fidelity assessment (O’Connor, Small & Cooney, 2007) was conducted to determine the allocative efficiency and assess the degree to which SPOR was implemented as planned and to determine the extent to which these implementation variances impacted the outputs, outcomes, and costs. In the case of the SPOR cost-efficiency analysis, the fidelity assessment is defined generally as a qualitative approach to assessing operational efficiency. This approach focuses on assessing the degree to which a program was implemented according to its initial plans, identifying variances in implementation, and examining these in order to determine the rationale for the variances and the effect they had on costs or on the achievement of outputs or outcomes. These approaches also allow for an assessment of the changes in delivery made by the program in its implementation approach and the impact that these had on costs or on the production of outputs or achievement of outcomes.

A proportion for operational efficiency was calculated annually for SPOR by dividing the total administration costs (direct and indirect) by the total SPOR expenditures (administration costs and grants and awards expenditures) (Exhibit 23).

As SPOR core elements have stated requirements for contributions for partnership funding (see Section 1.1), the extent of external partner contributions to SPOR were examined by tabulating applicant level partner contributions from 2010-11 to 2020-21, as provided in the applications. Partner contributions included cash and cash equivalent in-kind contributions for the full timeframe of the respective investments. A ratio of CIHR to partner contributions was calculated by SPOR element.

2.2 Data Analysis

Technical reports were prepared for each data source. For the data sources that included interviews, interview notes were prepared for individual interviews conducted and were then summarized and consolidated into an Excel database. Summarized notes were organized by question as presented in the interview guide and then mapped to the corresponding evaluation question. Questions were laid out in rows and the interviewee names formed the columns. A multi-stepped approach was used for the analysis. The first step was to complete a review of all interview summaries. This review provided the analyst with a preliminary understanding of the issues arising from the interviews. The next step in the process was a detailed review of the interview summaries looking at each interview question, or logical groupings of questions, noting keywords and statements and identifying common themes through the content analysis. Finally, findings were aligned by summarizing findings for each evaluation question.

In the development of the findings associated with the interviews, the analyst took into consideration the number of people or percentage of people who provided a specific response, comment or discussion along the same theme to understand shared or similar opinions across the group. Additionally, where there were rating questions associated with open ended questions, the analyst compared the qualitative findings with the quantitative findings to qualify coherence in the results and assess internal consistency.

For the purpose of this report, the following terminology is used to specify if there were single ideas or ideas shared by more than one individual:

- None (0 or no)

- A few (~20%)

- Some (~40%)

- Many (~60%)

- Most (~80%)

- All (100%)

Caution should be applied in over interpreting the magnitude of specific perspectives; a lack of response by a participant may not mean they do not have an opinion or similarly, an opinion by a few participants may not be shared by many more participants. Additionally, not all interviewees answered all questions. The number of respondents differs for each question and the analysis was performed based on the responses received for each question separately. As a result, the magnitude of responses presented in this report is based upon the sample of interviewees providing feedback for each relevant question. The average response ratings have been calculated as a standard weighted average based on the number of respondents.

A similar process was used to prepare the overall evaluation report, where each technical report was reviewed to identify logical groupings of findings across data sources noting keywords and statements and identifying common themes through the content analysis. Finally, findings were aligned by summarizing findings for each evaluation question and then rolled up to reflect the three evaluation issue areas.

2.3 Strengths and Limitations of the Evaluation

2.3.1 Strengths

Early stage of implementation. The evaluation was conducted at a time early enough to collect real-time feedback illuminating potential areas of opportunity to influence ongoing delivery. The evaluation was designed to focus on learning, while still measuring progress towards outcomes (measurable change).