Developing a method to predict preterm birth

July 22, 2020

Pregnancy is a complex process that relies on intricate coordination between the fetal membranes surrounding the baby, and the different parts of the uterus including the uterine muscle, lining, and uterine neck, cervix. In a healthy pregnancy at around week 40 the uterus contractions begin, the membranes break, and the cervix becomes extremely soft and then dilates to allow for the birth of the baby.

Each year in Canada approximately 30,000 or 8% of infants are born preterm – at less than 37 weeks of gestation. Infants born preterm can spend months in the neonatal intensive care unit, and are at increased risk of death and both short- and long-term health problems.

At least half of preterm births happen spontaneously for unknown reasons. There is currently no way to identify women who will deliver preterm and there are no effective treatments for women who are at high risk of a preterm birth having previously delivered one or more babies preterm.

One key to understanding preterm birth is the cervix. The cervix connects the main body of the uterus to the vagina and forms a natural barrier to protect the fetus from the hostile external environment. This barrier is essential for keeping the uterus closed to prevent ascending infection and maintaining the pregnancy. A short cervix measured by ultrasound is one of the only screening methods linked to preterm birth. Even so, only 27% of women with a short cervix deliver their babies preterm.

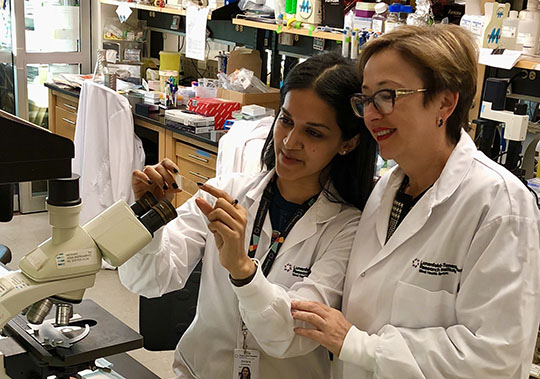

To find a method to predict preterm birth, Dr. Oksana Shynlova from Sinai Health System, who was awarded a CIHR-IHDCYH Preterm Birth Catalyst Grant, is working to address critical questions about how the cervix changes during term and preterm birth. She is using both animal models and imaging tools, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to study the cervix in pregnant women.

“Our study examines the reason the cervix dilates prematurely, in particular the link between structural changes in the cervix and the readiness for delivery (term and preterm). We speculate that bacterial infection inside the uterus or the vagina leads to premature cervical changes causing onset of preterm labor. These cervical changes may also happen spontaneously, without infection,” says Dr. Shynlova.

Studying the cervix is extremely challenging because of difficulties with both visualizing the cervix and timing assessments. For these reasons, the cellular structure of the cervix and any changes that occur during both term and preterm deliveries are unclear.

Similar to humans, the mouse cervix has two different regions: the top part close to the uterus is called the endocervix, and the bottom part close to the vagina is called the ectocervix. Dr. Shynlova and her postgraduate student Antara Chatterjee, are analyzing the cellular changes in the cervix of mice that deliver at term, preterm as a result of infection, or spontaneously preterm.

Using an imaging technique called micro-MRI in mice, along with analysis of gene expression and cervical cellular anatomy, Dr. Shynlova’s research has revealed two important findings. The first is that the top part of the mouse cervix has more muscle tissue than the bottom part, which may help keep the cervix closed during pregnancy to protect the fetus. The second finding is that the cells in the cervix, particularly the top part, lose structural integrity in preparation for labor. Together, these findings suggest that the top part of the cervix is essential for preventing preterm birth, and the timing of cellular changes in the cervix is critical for predicting onset of labor. Most importantly, the findings indicate that imaging the top part of the cervix with MRI may be able to predict the onset of preterm labor.

Motivated by her findings in mice, Dr. Shynlova is currently working to test whether MRI imaging of the top part of the cervix in healthy and high-risk pregnant women can predict preterm delivery.

“This will improve surveillance of at-risk pregnancies and promote research into therapeutic options for prevention of preterm birth in high-risk women who have already delivered a preterm baby,” says Dr. Shynlova. “If our hypothesis is supported, this novel approach to the care of women at risk of preterm birth will have the power to interrupt the vicious cycle of disease.”

- Date modified: